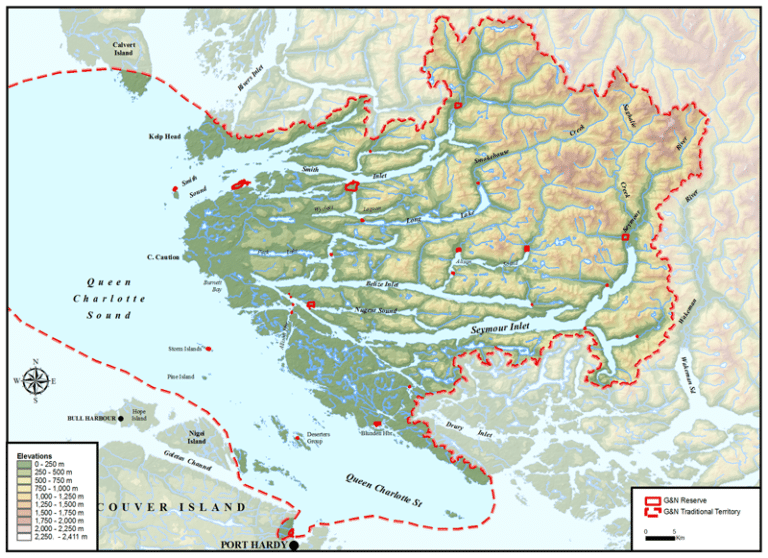

If you come to the North Island, to the settler community of Port Hardy, you may not even notice the small bridge at the northeastern tip of town that takes one into the Tsulquate Reserve, home to the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations. These had been separate Nations. The Gwa’sala had a winter village in Smith Inlet, and the ‘Nakwaxda’xw had a winter village in Ba’as (Blunden Harbour) and others in Seymour Inlet. Despite losing many people in the epidemics of the 1800s and early 1900s, because of geographic isolation, their traditional culture was mostly maintained. They had less involvement with the settler’s political and religious authorities than the Kwakiutl peoples, whose traditional territory is occupied by Port Hardy. However, by 1929 the Gwa’sala and the ‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations were impacted, when their children were removed to St. Michael’s Indian Residential School.

The Nations were self-sufficient. There was water and land and enough creation to have everything they needed. They traded goods between Nations and held Potlatches. They fished and harvested seaweed, seagull eggs, shellfish and more.

The problem for the government was that it was expensive for them to offer resources such as access to health care. In the 1960s, as part of their efforts to assimilate Indigenous peoples into settler culture, the Canadian government, and the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development in particular, began to push the Gwa’sala and the ‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations to relocate and integrated into the Kwakiutl First Nation. The government knew that this move would make it less expensive to provide health care, education and access to resources.

The Canadian government used both threats and incentives: if the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations stayed where they were, they would not get any help building houses, schools and medical clinics. If they moved, they would get all these things and more: a community hall, a place for their boats, good jobs and a good school in Port Hardy for their kids. With this pressure, the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations amalgamated and agreed to move. However, the government supposedly didn’t have enough money to keep their promises and told the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations that only a few people should move, and that others should come later. That is not how these Nations work: they do not leave people behind.

In 1964, at the end of their fishing season, the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw moved from 350,000 square kilometres of traditional territories to the 0.59 kilomtres squared Tsulquate Reserve, which had been a campground of the Kwakiutl First Nation, who reside at Tsaxis (Fort Rupert). It is rugged land with big rocks and steep hills.

Approximately 200 people made the move. They arrived to find four houses that were incomplete, with no running water or toilets. They did not have any safe places to moor their boats, meaning that many were destroyed in the river. Many families were forced to live in these uninsulated boats; they were overcrowded and without resources. The children were sent to school with strangers who spoke a different language and lived a different culture. Their traditional ways were not possible on the Tsulquate Reserve. There was no going back though: the Canadian government, through the RCMP, had gone to their territories and burned down their villages, including their big houses (Gukwdzis), their belongings, their valuables and their regalia.

The Kwakiutl First Nation did not appreciate the amalgamation with the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations and they petitioned to be separated, since the Nations were not benefiting from this agreement, only the Government of Canada was. The Kwakiutl were successful in this bid.

In 1970, the government investigated what had happened and acknowledged how horribly wrong it had all gone, and that the promises that had been made had been broken. In 1974, Alan Fry, a settler who worked as an Indian agent, wrote a book about the the Tsulquate Reserve and called it How a People Die. There were about 200 people living on the reserve and he did not expect that they would survive this experience.

There is no doubt that this traumatic experience has had serious impacts on the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations. Looking at the challenges facing these Nations today, it should be acknowledged that it is not a homelessness problem here, it is a houselessness problem. The people of these Nations have a home — the 350,000 kilometres squared of lands and waterways they were enticed from. It is a different scenario than for much of the country, where land was stolen for the purpose of settling other (white) people. Land was stolen because the federal government could save some money while also working to assimilate them.

Intergenerational trauma and the impacts of colonialization and racism are being felt by the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations. There are high rates of substance use disorder and deaths by suicide. On March 1, 2024, a state of emergency was called after 11 people had died since January 1, 2024. The abuse of power at St. Michael’s Indian Residential School has meant that sexual violence and intimate partner violence also factor in— shame and trauma undergird the realities of addiction and suicide. The Port Hardy Hospital has the capacity to offer Forensic Nursing Services 24/7 for anyone 13 and up who has experienced these sorts of assaults. A community of this size (Port Hardy has a population of 3,902) should not need this service 24/7. The people who have died are buried in the Port Hardy cemetery, not in their homelands.

But here is the thing: Alan Fry had it wrong. 60 years after the relocation (1964-2024) the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw have not died out or disappeared. In 2010, a Comprehensive Community Plan was developed, and the Nations are now in stage five of the treaty negotiation process (stage six is implementation of the treaty). The community is working on language and cultural reclamation (in the 2016 census the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw numbered over 1000 (on and off reserve), but just 30 people could speak Kwak’wala). They are passing on the traditions and teachings of the ancestors. They have established guardians to care for their sacred places, lands and waters on their traditional territories. They are building strong families.

In 2012, the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Nations worked with an Anishnaabe filmmaker, Lisa Jackson, and released a film called How a People Live. The film uses archival footage from over 100 years ago, interviews with people, and a trip for some members of the Nations to visit their homelands. There is resiliency here, with Indigenous-led efforts to provide resources and a better future.

Intergeneration healing is happening. There is movement for the creation of culturally safe supported housing, youth supports and more. Now the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw number over 1000 people (on and off reserve). Building is happening in their traditional territories with cabins at Ba’as and Takush. Much is being done to improve food security including access to traditional foods. They now have their own schools, an Elder’s Centre, a medical clinic and more. There are supports at places like North Island Building Blocks, Sacred Wolf Friendship Centre and the Ḵ̓wa̱la’sta Healing Centre. They have established the K’awat’si Economic Development Corporation, whose work includes the building of Kwa’lilas Hotel, as well as other construction projects and operations throughout the North Island.

In December of last year, the hereditary chiefs and representatives reclaimed some of their kikasu (the treasures of their ancestors) from the Royal BC Museum. This included masks, regalia and carvings. These items will be part of the opening ceremony of the Gwa’sala-‘Nakwaxda’xw Gukwdzi (Big House), which is set to open later this year. These Nations, after 60 years, are going to have their own Gukwdzi. The healing from their cultural genocide will continue. This is the place where people learn to dance and sing, to tell their traditional stories and to speak their languages. This is the place where they feed and connect to their ancestors. Potlatches, naming ceremonies, weddings and funerals will be held there, and it will serve as a meeting place for decisions and governance. (All these years they have been holding these events in the neighbouring Gukwdzi in Tsakis, or in Wakas Community Hall, which is a gym with a cement floor.)

There is so much hope for the future. There is so much good work being done to remedy the trauma caused by Canadian society. In the work towards reconciliation, the Anglican Church needs to be actively engaged in supporting the initiatives of the First Nations, whose lands and waters we occupy. All people of faith need to be pressing all our elected leaders to fulfill their duties and responsibilities as outlined in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, the 94 Calls to Action and the 231 Calls to Justice of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

More information can be found in the links throughout this article.