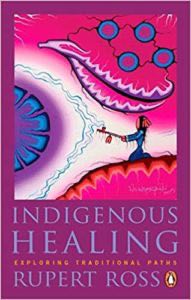

Book Review: Indigenous Healing: Exploring Traditional Paths by Rupert Ross. Toronto, Penguin Canada, 2014.

Book Review: Indigenous Healing: Exploring Traditional Paths by Rupert Ross. Toronto, Penguin Canada, 2014.

After hearing Martin Brokenleg, a priest and prominent psychologist specializing in Indigenous trauma and resilience, recommend this book, I ordered it and was surprised to find that it’s written by a retired assistant Crown attorney, who is non-Indigenous. Ross is also the author of two previous books on related topics and writes with humility, empathy and insight into this challenging area. The book has three parts: 1) Stumbling into a World of Right Relations, 2) Colonization and 3) Healing from Colonization. In his introduction, Ross writes that he hopes to set a stronger tone of mutual respect for greater understanding in the ongoing truth and reconciliation process.

In Part 1, Ross first deals with relational justice. In 1992 Ross had been seconded to the Aboriginal Justice Directorate and assigned “to explore the aboriginal assertion that, for them, justice was primarily a healing activity, not one of vengeance or retribution.” After attending some sweat lodges, Ross learned the importance of a focus on “All my relations” — indicating that everything is interconnected. Ross found that offenders often seemed indifferent to how their actions impacted others and needed to be shown that connection. He came to understand that “seeing relationally” meant looking at how the crime came out of all the offender’s relationships, and in turn affected those relationships. In the third chapter of Part 1, called “Moving into Right Relations,” Ross addresses Indigenous cultural and spiritual practices and how they intersect with notions of justice. I thoroughly enjoyed the teachings here and learned a great deal about these interconnected areas. I too have attended sweat lodges (with the Tla’amin Nation) and was in awe at being told that the steam from the rocks was the breath of our ancestors.

Part 2 on “Colonization” was the most painful part of the book, and rightly so, given the pain that Indigenous Peoples have experienced, especially through Canada’s residential school system. Chapter 4 deals with the many sources of harm and covers topics including “Diseases,” “The Denigration of Women and their Roles,” “Legal Discrimination” and “Relocation of Families and Communities.” The book then moves more directly into a focus on residential schools in Chapter 5. Ross starts with the provocatively difficult first section entitled “The Children Were Prisoners, Not Just Students.” Ross then extrapolates on this theme and details the abandonment, poverty, disease, denigration and abuse that the children suffered from. Like many others, I’ve read plenty of stories from residential school survivors over the years, but Ross presents this material in a particularly compelling way.

Chapter 6 moves on to explore the psychological damage inflicted on Indigenous Peoples and the ways this damage manifests itself through PTSD, emotional suppression, shame and alcohol and drug abuse disorders. The section on “Learned Helplessness” was especially helpful as Ross cites various psychologists to help explain how the experience of residential schools, where a child’s needs, fears and concerns were either ignored or punished, can make people or groups become passive, inactive and hostile. The last two chapters of Part 2 deal with the experience of residential school survivors once they returned home, as well as the impact of the Sixties Scoop and incarceration. Michelle Good’s multi-award-winning 2020 book Five Little Indians is much more understandable to me now after reading Ross’s “Going Home” section. The forces aligned against these older teenagers after leaving the immense trauma of residential schools is a complex knot of intertwined and often overwhelming challenges. And the “Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” section includes a focus on intergenerational trauma — a topic that Dr. Brokenleg has taught and written on extensively.

Part 3, called “Healing from Colonization,” begins with an appropriately humble chapter on “How to Begin.” Then Chapter 10 looks at three specific healing programs: the Hollow Water Community Holistic Circle Healing Program, the National Native Alcohol and Drug Addiction Program (NNADAP) and the Redpath program. Ross describes these three programs not as ends in themselves, but rather as important examples of the ways that traditional Indigenous healing ideas can be incorporated as further programs are developed. The last chapter (11) provides examples of Indigenous approaches to healing, including group healing, restoring the emotional realm, ceremonies, respecting the worth of everyone and the role of land in healing.

Then Ross writes a beautiful conclusion, including stories of his own awkward attempts and failures to live up to his goals of learning and incorporating many aspects of Indigenous healing into his own life and work. In reading this excellent book, and despite how overwhelming the details were at times, I cherish especially the idea of finding our place as part of the interconnected web of all beings. This idea is so important for the Earth’s survival. To me, this book on Indigenous healing had so much to say about how all of us need to live in a more respectfully sacrificial way on Mother Earth, conscious of how all our actions have an interconnected impact for good or ill. So let us choose wisely!