The Diocese of Islands and Inlets has title to 46 church properties. How these properties came to be part of our diocese are stories we must learn and reflect upon. I am grateful to Jesse Robertson who is working with our archivist, Chance Dixon, on a project to document the history of some of our property holdings. We know that many of them came to us as donations from settlers.

We are grateful for the generosity of those settlers. However, we cannot ignore the fact that the ways in which settlers came to have titles to lands in this part of God’s creation was extremely violent and colonial.

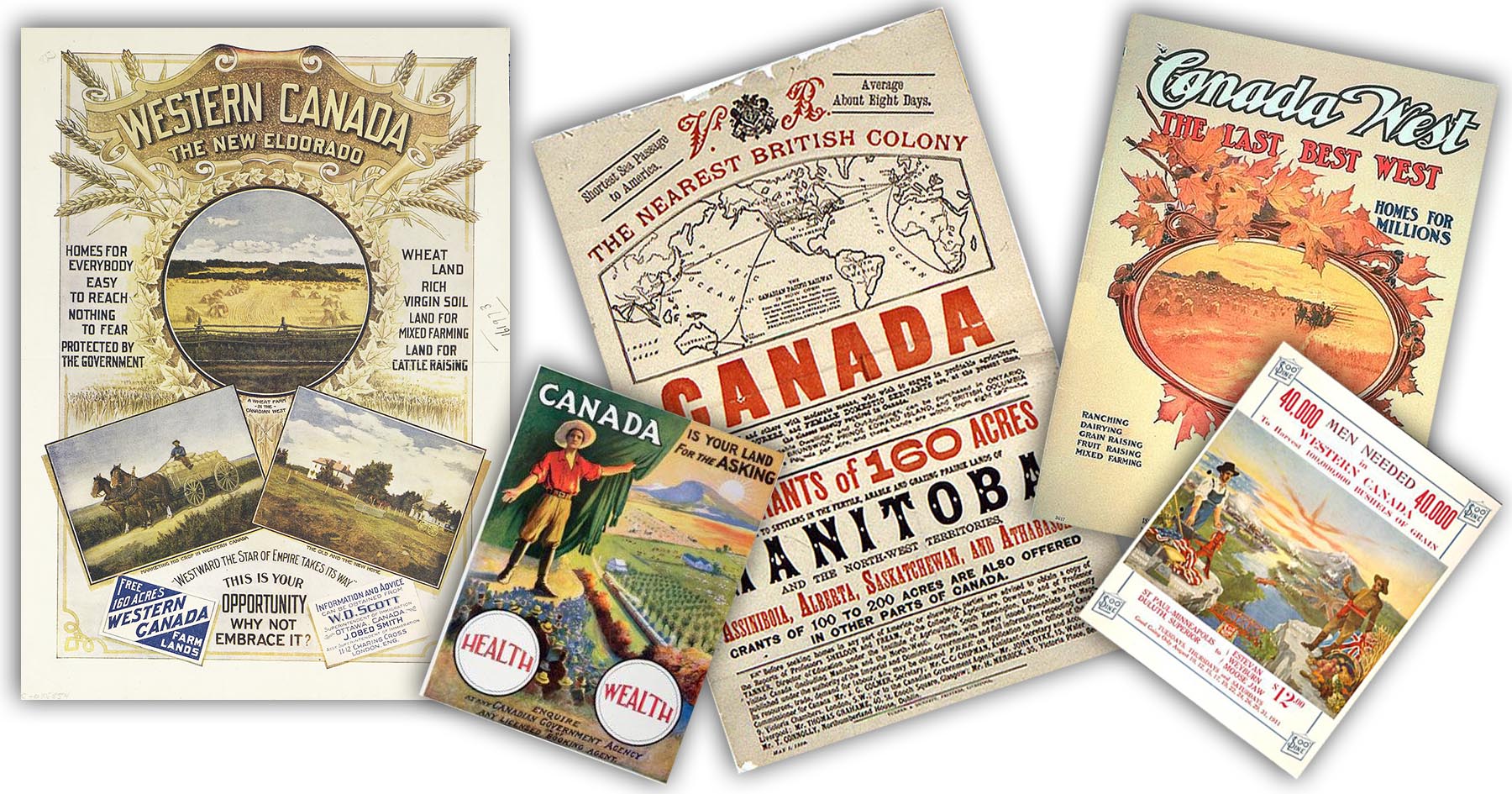

The colony of Vancouver Island was established by Britain in 1849. It was then leased to the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) for 10 years for the nominal annual fee of seven shillings. The HBC then began selling parcels of the colony to settlers by acre, with a minimum purchase of 20 acres.

Parallel to these land sales, James Douglas, in his role as governor, was also busy at work negotiating and imposing what were dubiously titled treaties. Lest there was any doubt about the harmful nature of these agreements, the text below formed the basis of each of them:

“The condition of our understanding of this sale is this, that our village sites and enclosed fields are to be kept for our own use, for the use of our children, and for those who may follow after us; and the land shall be properly surveyed hereafter. It is understood, however, that the land itself, with these small exceptions, becomes the entire property of the White people for ever; it is also understood that we are at liberty to hunt over the unoccupied lands and to carry on our fisheries as formerly.”

Most of our properties are on Douglas Treaty lands as the pacts covered what is now Victoria and Saanich, and also the west shore (what is now the Nanaimo area and the region around what we now call Port Hardy).

Within a short time however, the treaties were ignored. Village sites and fields were pre-empted. In 1860, Douglas introduced a Land Registry Act that allowed settlers — but not First Nations — to appropriate up to 160 acres of crown land on Vancouver Island by simply making improvements such as clearing fields or building a cabin. Many of our diocesan properties were gifted to us by such settlers. Our history as a diocese cannot be separated from the colonial past of this land.

In early May, the diocese, as part of the John Albert Hall lecture series, is hosting a three-day event entitled Land, Law, Religion and Reconciliation at the University of Victoria. I hope that as many people across the diocese as possible will join us for part of or the entire event. Besides attending in person, participants will also be able to watch some of the keynote sessions online on Zoom.

We are at a point in history when we need both to examine and learn the colonial history of our land and to faithfully discern what we might do next. Ageing church buildings and declining attendance mean that the idea of redeveloping our properties is increasingly on our minds. We cannot consider such projects without the very real work of truth telling and reconciliation. We know that there are no easy answers to how to best steward the land for future generations.

We cannot undo the past, and yet we must faithfully discern what God is calling us into in the future. Also, we can no longer pretend that the history of this place is of virtuous and heroic settlers who had “tamed a wilderness.” We must instead recognize and repent for the tremendous violence and desecration that are a part of both our past and our present. The words of Jeremiah echo across time and space, reminding us that God does see, and that God is calling us to new ways of being in relationship with the land and with our neighbours:

How long must the land cry out in mourning,

the grasses of the field wither and bake in the sun?

The birds and wild animals have simply vanished,

all because of the wicked living here —

Because they say, “God does not see what will become of us.”

(Jeremiah 12:4)