During their time at St John the Evangelist, Montreal a few years ago, I had the pleasure to know Arlie Coles and Kieran Wilson. Both had come to the city and to the parish from afar, and both were greatly devoted to the Anglo-Catholic worship of St John’s as parishioners, altar servers, and members of the wider Anglican Communion.

Arlie and Kieran remain committed to High Church beliefs and practices. Recently, I interviewed them about a new enterprise they are both involved in — the creation of a publishing company St Lazarus Press which specializes in printing Anglo-Catholic books. Besides discussing this exciting new endeavor, Arlie and Kieran talked about their journeys of faith, their lives in their current parishes, and their insights — from their perspective as millennials — about the current state and possible future of the Anglican and Episcopalian Churches, particularly in regards to the special traditions they are faithful to.

****************************

How did you Arlie (from Texas) and you Kieran (from Victoria) come to Montreal? What attracted you to St John the Evangelist, and were you “cradle Anglicans/Episcopalians” or did you come into the faith later on?

AC: I came to Montreal to study at McGill University. I am a “cradle Episcopalian,” having grown up (as all Episcopalians do) in the Prayer Book tradition and (as some Episcopalians do) serving at the altar. By the time I came to Quebec, I was mid-climb up the ladder of appreciation for the historic aspects of traditional Christian rite and ceremony, and spent some time trying to navigate and understand the similar-but-different landscape of the Anglican Church of Canada. Episcopalians did not spin off another book from our Book of Common Prayer at our last revision, which kept historic and contemporary prayers together in one volume; so for some time I naïvely assumed that the Canadian situation was analogous and that all the parishes I’d visited simply used some contemporary “half” of the Book.

Upon visiting the Church of St John the Evangelist in Montreal in an effort to see more of the diocese, I realized that was wrong: here it all was, the whole array of traditional rite and ceremony that had so deeply formed my faith throughout my upbringing — which, I then understood, was rare to find in this form in the Canadian church, given the separation of the Book of Alternative Services and the Book of Common Prayer. For me, St. John’s was an immediate and natural fit. I was instantly welcomed into this community that owned and loved this ritual distinctness; that loved Jesus, especially seeking Him in the eucharist; and that loved their neighbours, making every effort to care for the poor and everyone they came across. At a time in life when many begin to wander, St John’s kept me fixed and drew me closer to God.

KW: I moved from Victoria, where I was born and raised, to Montreal in 2013 to start my undergraduate studies at McGill. When I came to faith and to Anglicanism specifically in my teens, I was immediately drawn to the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer, and over the course of a few years, I came to discover the depth and richness of the Anglo-Catholic intellectual and spiritual tradition. So the Church of St John the Evangelist, a bastion of Prayer-Book Anglo-Catholicism, was a natural parish home for me in Montreal. I was excited to live the pattern of life and worship — complete with daily Mass, high celebrations on feast-days, a tradition of service to the poor and to the broader community — that I had read about in books!

Most people think that the appeal of Anglo-Catholicism is primarily aesthetic, and, indeed, I found the liturgy and architecture of St John the Evangelist strikingly beautiful; but what struck me most was the seriousness with which parishioners treated the truths of the Christian faith and the Church’s sacramental worship. People believed not only that the articles of the Creed were true, but also that the sacraments were God’s own, genuine work in their lives. The realisation that others thought as I did in this regard has been my greatest buttress and comfort in living out my faith. I haven’t worshipped regularly at St John’s since 2017 (after various changes and chances, my wife and I finally settled in Victoria again in 2020), but I still regard St John’s in many ways as a spiritual home, not least because it is where I first truly learned the Catholic faith. As the famous poet John Betjeman put it, for me my years at St John’s “were the waking days, / When Faith was taught and fanned to a golden blaze.” And so, when I heard that St Lazarus Press had been launched to support the parish’s work, I jumped at the opportunity to lend a hand.

What was the genesis of St Lazarus Press? How did that come about?

AC and KW: St John’s has a historic building that has caused it financial challenges in recent times. In response, the parish community, which had remained as tight-knit as ever through the pandemic, banded together with friends of the parish to launch a number of creative initiatives, including St Lazarus Press. The goal was both to raise a bit of money and to secure St John’s ability to keep being the unique institution it is in Quebec — the steward of an Anglo-Catholic, Prayer Book tradition and an ongoing outpost of God’s presence in the city. When considering the parish’s vast archives and its historic status, the idea to publish came quickly, and those willing to pitch in followed. Publishing is a way for the parish to perpetuate its tradition and share what it has with others.

After creating the Press, how did you decide what titles to publish?

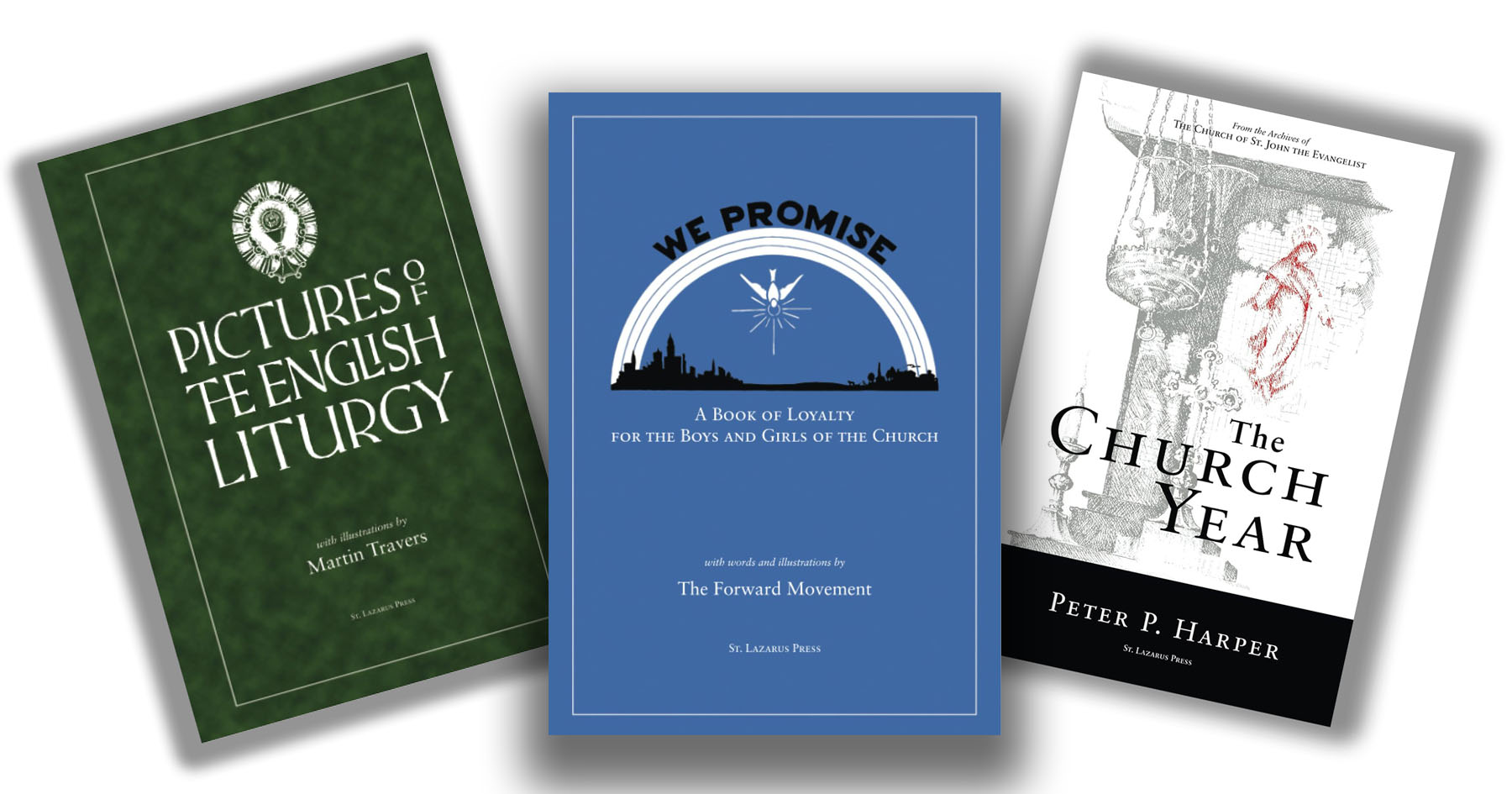

AC and KW: The parish had several ideas nearly overnight! We decided to begin with a reprint of Martin Travers’ Pictures of the English Liturgy not only because it is well-loved in the Anglo-Catholic community, but also because, simply, some of its artwork has adorned the Mass bulletins at St John’s for some time — it seemed like a fitting first extension of the tradition at St John’s into the wider world. We followed this with a reprint of We Promise, an Episcopal children’s book, as a way of perpetuating this tradition directly to a future generation and at the request of some at the parish who desired something to share with children and grandchildren.

In the meanwhile, we worked on The Church Year, a guide to the church calendar and the Press’ first offering from St John’s parish archives themselves. This book was assembled from among the works of the late beloved parish historian Peter Harper, and well represents St John’s habit of keeping its tradition going by teaching it to others. Broadly speaking, our criteria for choosing titles to publish are: their relevance to the Anglo-Catholic and Prayer-Book traditions both in Canada and elsewhere; their connection to St John’s and its history; and their contribution to the Press’s project of furnishing intellectual, spiritual and liturgical resources for those seeking to rediscover and reinvigorate the theological and devotional heritage that St John’s embodies.

What goes on behind-the-scenes in creating a book? Is it difficult?

AC and KW: Books go through several stages before publication. For projects not originating in the parish archives, the first thing is to secure the rights to publish; this can involve hunting down international copyright details, legal documents, or even individuals possessing the rights or other helpful information.

Significant time is spent editing the manuscript, from high-level developmental editing (what order should all the pieces be in?) to low-level copy editing (where many hands and eagle-eyes make light work!). We then try to consult as many editions of the original work as possible, whether from the parish archives or from outside sources, to get a flavour of its overall creative design, aiming to reflect and refresh it in our new edition.

Books with illustrations require special attention, involving either digital retouching of the originals or selecting suitable substitutes. To keep costs down, most of the typesetting process takes place in LaTeX, an open-source document preparation tool. Once we are satisfied that the manuscript’s content is robust and its layout is beautiful, we design a cover and send the book to the printer. Amazon has served the Press’ needs for this well, but we would love to expand into different types of binding, paper, and book trim size. The process doesn’t end with publication, of course — then the Press has to let the public know there is an exciting new book available for purchase!

Having published three books so far, what others would you like to bring into print?

AC and KW: The Press has several projects that will appear in the new year, including a devotional book centred on the Blessed Sacrament and a reprint of a well-loved liturgical history by a famous author-priest. We’re also excited to bring forth more material from St John’s rich parish archives, including a unique volume on the parish’s rector-founder, Fr. Edmund Wood, that sets priceless bits of Montreal history in with the larger story of the growth of North American Anglo-Catholicism. In the future, the Press would like to work further with French-language Anglican materials as well as with the Book of Common Prayer (1962) itself more directly. This is our way of doing our part to maintain that portion of our received tradition — St. John’s is currently the only full-time Prayer Book parish in all of Quebec.

For our readers interested in publishing, what advice would you give?

AC and KW: The barrier to publish is lower than ever before! That means the field is also more crowded than ever before. The right market, however, can detect labours of love. Pour your love and enthusiasm into whatever part of the process interests you — editing, design, illustration, typesetting, marketing — and it will show. For religious publications, the barrier many Christians feel to promoting the fruits of their labour, out of a well-intentioned desire to not let the left hand know what the right hand is doing, must also be mitigated. Don’t be afraid to let people know what you’re putting into the world, particularly if the hope is for it to strengthen or educate others in the faith. They must know about it in order for that goal to be met.

As committed Anglo-Catholics, how are you involved in the spiritual and community life of your respective parishes that you now attend?

AC: At the Church of the Incarnation, the moderately High-Church parish in Dallas, Texas where I currently attend, many parishioners are recently arriving from a more evangelical or nondenominational background. My “cradle” upbringing combined with the deep immersion in Catholic liturgical patterns I experienced at St. John’s sometimes equips me to answer questions that newcomers have about Anglican life and practice. Whether it is details about specific forms of altar service, explanation of the contents of the Prayer Book and its various idiosyncrasies, or historical tangents about the various developments in recent decades in the life of our Church — getting to share these meaningful things with others who are seeking our particularly deep-rooted and sacramental form of Christian life is a joy.

KW: My family are parishioners at the Church of Saint Barnabas in Victoria, where until 2022, I was both administrator and pastoral assistant. My involvement in parish life has changed enormously over the past two or three years for various reasons, not the least of which is my wife and I welcoming our daughter in the autumn of 2022. Since my baptism at 16, I’ve tended to be very involved in parish life wherever I end up, but the demands of parenthood and a new career have made maintaining my usual level of involvement in parish life rather difficult, and I have had to cut back my parish responsibilities drastically over the past several months. Lately, I have been directing my energy and attention to building up my own domestic church. I try as often as possible to say Morning and Evening Prayer with my daughter; I’m not sure how much of it she understands just yet, but she loves playing with the ribbons of my Prayer Book, so I think we’re off to a good start. Nature perfects grace, after all, and there is nothing more natural than a one-year-old delighting in dangling, parti-colour bits of cloth! My and my family’s participation in the life of the Church has become more private, more intimate, more homely (in its literal sense used often by Mother Julian of Norwich) than it has been in the past.

I’m curious, how do you see High Church Anglicanism/Episcopalianism in Canada and in the United States today? How do we make it relevant and meaningful to younger generations who will hopefully carry on the faith and its traditions?

KW: I’ve been thinking a lot about these questions lately, so I’m afraid this will be a rather long answer. On the state of High Church Anglicanism or Anglo-Catholicism in Canada today, I must confess I am not especially optimistic. The Anglo-Catholic ethos entails, to my mind, the grounding of one’s individual and collective spiritual life in the Church’s sacraments. It is from the sacraments that the Christian derives strength to meet, as far as possible, the high calling of the Christian life, and it is around the sacraments, and especially the regular celebration of the Sacrament of the Altar, that the rest of one’s discipline of prayer is structured. Traditionally, though not without exception, the Anglo-Catholic sacramental ethos has been lived out in the context of the local parish, a unit of ecclesiastical organisation imperilled by the Anglican Church of Canada’s demographic collapse. In many rural places, parish structures will likely disappear in the next 15 to 20 years, as they have already in many smaller towns. I have spent some time in rural parishes in different parts of the country, and it seems to me that the fact these parishes have managed to survive as long as they have is a sterling testament to the dedication of their (often lay, often over-stretched) leadership.

Parish life will likely continue in reduced circumstances in larger population centres, but then these population centres, at least in British Columbia, are increasingly and apparently irremediably unaffordable, especially for younger people. It is likely that my family’s future will be in a small town, and, in consequence, it is likely that we will not have access to parish life and to the regular round of sacramental worship and fellowship with our “even-Christians” that we have hitherto found in parish communities.

This is a source of great sorrow for me and for many others, of course, but I don’t think it is cause for despair for the Anglo-Catholic tradition. I was drawn to Anglo-Catholicism as a former “none” precisely because it resonated with me at a level of which I was scarcely conscious at first. It speaks to something deep in our being, something, dare I say, for which contemporary sensibilities and even contemporary theologies cannot account. It gives expression to a sense of wonder — the horizon of which we can always see but which always recedes from us and confounds our attempts to express it adequately. I suspect that the profound resonances I have found in the Anglo-Catholic tradition will be felt by many others after me, until the Lord comes.

I certainly hope that this tradition will thus resonate for my own family, and, while I have no control as an individual over Anglicanism’s institutional and demographic trajectory in this country or in this diocese, I can control how I respond to these trends. The first step, it seems to me, is building as robust and complete a life of family prayer as possible. Perhaps it’s impossible to attend Mass on high feast days, perhaps there is no church within reach for Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve, perhaps, even if there is a church within reach, there is no priest to celebrate the liturgies of the Triduum. Even so, we can always say (or sing!) Mattins and Evensong, sing carols to herald the Lord’s coming in the flesh, or recite with gravity and solemnity the Litany and the office of Antecommunion on Good Friday. These private devotions, even when celebrated according to the rites of the Church, are of course no substitute for truly common prayer amongst God’s people; but they can keep the lamp of faith burning through the long night of exile that seems to await us, when common prayer will be a treat reserved for the occasional visit to the city. Private prayer is what sustained the people of Israel during the Babylonian Captivity, when for a whole generation and more the Temple was but a heap of stones and its altars were cold and bereft of offerings. “How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?” How indeed, and yet the attempt — a fine piece of personal devotional poetry — furnished us with a psalm.

To sum up what has been rather a lengthy answer to your question, I think the best way to preserve the High Church tradition is by living that tradition as authentically and fully as circumstances allow. That’s precisely the point of St Lazarus Press, to keep an authentic Anglo-Catholic witness alive in tandem with, or if need be in the future, in place of ordinary parish-based ministry.

In terms of making the Anglo-Catholic tradition attractive to younger generations, I think, on one level, that we do not need to make it attractive and relevant; it is already relevant and attractive, because it speaks to something deeper in our beings than mere passing fashions. This, at least, has been my experience. I have been deeply influenced by the thought of Fr. Martin Thornton on this question. He saw the parish as a “remnant,” like the remnant of ancient Israel who kept the faith alive in Babylon and returned to take possession of the land of promise, a nucleus of faithful souls who, to use Saint Paul’s metaphor, “leaven the whole lump” of dough that is the community around them. In our context, I think we must move on from seeing this “leavening” as the vocation of the parish; it is now the vocation of each Christian family, indeed of each Christian heart, until God shall be pleased to “turn again the captivity of Sion.” We just have to be who we most truly are — that is, who God enables us to be — and leave the survival of Catholic Anglicanism, and, indeed, of Christianity more broadly, in this time and place to God’s good providence.

AC: As a representative of Canada’s bigger and louder neighbour to the south, I am somewhat more optimistic than Kieran is here, though cautiously so. The Episcopal Church’s demographic decline continues slightly behind that of the Anglican Church of Canada, and many in our house are beginning to speak plainly of the coming collapse of parochial life; but I perceive several opportunities to begin righting the ship.

Having grown up through the strife and schisms of the 90s-00s, I have been most heartened to note a flourishing public resurgence of creedal orthodoxy in the Church. A non-negligible amount of good will flow from this re-centring alone, particularly as our country continues to move through a period of significant civil division, which has itself resulted in uneasy reorganization of ecclesial ground for many who are now seeking a more stable — we may say a more Catholic — form of faith. In this sense I fully agree with Kieran: there is no need to make our traditions attractive, as they are already deeply compelling even to young people on their own terms, but there is a great need to make our attractive traditions accessible to those who yearn for them but do not know they exist. It therefore seems to me like now, before the waters surge to their choppiest, is the best time to record everything we know in the interest of being ready. It is technically easier than ever to create resources for the church, whether liturgical, historical, or otherwise educational, should God in His good graces continue to cause some new subsection of the population to yearn for them. If various forms of the Anglican tradition are to be preserved in the Episcopal Church, including those from the particularly Anglo-Catholic wing, the deep institutional knowledge cultivated over decades currently locked in the collective minds of individual parishes must be made public and shared — that is the best way to ensure they live another day, whether by being directly passed to current parishes in need or, if need be, lying fallow for a time and being taken up by a next generation when possible.

Finally, our era’s high degree of technological interconnectedness (which skews the young, but is by no means exclusively so) will continue to change the shape of the church, often for the better. At a glance and on demand, I may now see and learn from any of the vast panoply of services or other materials from the major outposts of the Anglican Communion — an extravagant dream of any archivist from even one generation ago! Bonds of affection and exchanges of ideas and resources may be easily nourished across diocesan and even provincial boundaries, thanks to online communities that burgeon into networks of true friends who have the power to accomplish something in the Church together. At my most optimistic, I see this as a new angle on the very real unity of the Body of Christ; sharing our own practices with one another via these new channels helps build up the Body, sowing seeds whose reaping we may not see but that God may nevertheless use in His good time. The American Church and the Canadian Church are two obvious candidates for such a modern deepening of our existing partnership. To employ an American phrase first used in quite different circumstances, it seems to me that when it comes to the next 20 years of the Anglican Communion, we must all hang together, or, most assuredly, we will all hang separately.

For more information about St Lazarus Press visit: www.redroof.ca/st-lazarus-press