In 2021, Terry Wildman, who is of Ojibwe (Ontario, Canada), Yaqui (Sonora, Mexico) and European decent, published a translation of the New Testament that is intended to be “by and for the Indigenous Peoples of North America.” The translation, called the First Nations Version, is written in English, but is intended to reflect the idioms, speech patterns and rhythms of Indigenous languages and oral traditions. Wildman was supported in the writing of this translation by a translation council and Indigenous reviewers from different geographic regions. The First Nations Version of the New Testament has since sold hundreds of thousands of copies and a First Nations Version of the Psalms and Proverbs was published in August 2025.

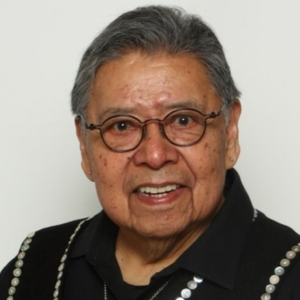

The First Nations Version is being used increasingly in Anglican churches in Canada. However, not everyone is supportive of the translation. Martin Brokenleg is an enrolled member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and was a professor of Native American studies at Augustana University in South Dakota for 30 years. He also served as professor and director of the Native ministries programme at the Vancouver School of Theology. He is an honorary assistant at Christ Church Cathedral and St Barnabas Church in Victoria. Below Martin shares why he is opposed to the First Nations Version. — Naomi Racz, Editor

I should begin by saying that I have discussed the First Nations Version of the New Testament with fellow Indigenous clergy mostly in the USA, since a full one half of The Episcopal Church’s native ministry is in South Dakota where I grew up and have family. I am minimally active in my retirement, mainly preaching at St Barnabas parish in Victoria and very rarely at the cathedral. I have not been a part of Sacred Circle for some time. This is due to my mobility issues and belief that younger people should be active in the Circle.

I was initially enthusiastic about such a version. I have always found Anglicanism to be Christianity in English clothing. That was a reason I explored another venerable tradition and was ordained in the old calendar Greek Orthodox Church for 15 years. I tried to find what in Christianity was not embedded in western culture. There, I found the faith embedded in Greek or Russian culture. I returned home to the Anglican church although it was still very English but was at least quite familiar. As a long-time professor of Indigenous studies, I can attest to an ever-increasing understanding of the unchangeability of culture. In the 19th century almost all scholars thought culture could be changed. I thought religion could be distinctive from culture but my 15-year exploration proved me wrong.

I find most Canadians in the church are now incredibly supportive of things Indigenous. I think this accounts for the enthusiastic welcoming of this text said to be an Indigenous version. I do not find it so and am more convinced that encouraging its use may deepen unfortunate racial stereotypes. One Indigenous priest who is very active in Indigenous communities, mainly urban, says this is the “Tonto Talk” New Testament. I agree with him.

This text is not published by any known biblical scholars who might enlighten a new translation. Finding the appropriate exegetical base with a Greek text is complicated enough. This version adds another layer of distance by use of names from 19th century literature with Indigenous characters. This requires a reader to learn yet another layer to understand the text.

Further, the diversity of cultural vocabulary in Indigenous communities makes it highly unlikely that more than one language community or one culture group can generate a version that might clarify the text for their readers and listeners. After all, anthropologists find more cultural variability among Indigenous North Americans than anywhere else in the world. This variability leaves a committee, such as the one that worked on this version, using what they believe to be general Indigenous terms that speak to more than one Indigenous group.

It takes only the slightest move to slide into the stereotypes we find in film and elsewhere. We may be familiar with the stereotypes of people with African ancestry perpetuated by Stepin Fetchit and Aunt Jemima. This Indigenous version of the New Testament is dangerously close and may even have crossed the line into that dynamic while supposedly portraying Indigenous culture. For that reason, I am totally opposed to any use of this version. The only factor that would worsen the use of this version is if that decision were not made by a totally Indigenous group of people.

I am content to recognize that the texts we use are Greek and from another culture. I am also content that I belong to a community that is essentially The Church of England. Cultural differences can be managed by Indigenous people. My medicine man grandfather was fluent in five Indigenous languages. Use of this version does not speak to Indigenous people in the church as much as love, caring and justice do.