If, in the year 1860, you were to stand on Beacon Hill in Victoria and look south across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, you would see in the Olympic mountains the westernmost rampart of a continent-spanning, slaveholding republic. In that last full year before the outbreak of the American Civil War, the traffic in Black slaves was carried on in the fifteen so-called “slave states,” but the “peculiar institution” — the tidy euphemism with which slavery was cloaked — was not confined to those states alone.

Manifest destiny, the notion that God had ordained the United States to spread the blessings of freedom and democracy, at the point of a bayonet, if necessary, had carried the American republic to the shores of the Pacific — and slavery with it. Slavery was practised even in the “free territories” of the American Pacific coast. The streets of Victoria resounded on at least one occasion with merrymaking for a slave who had slipped across the strait from the “free” territory of Washington to deliverance from servitude in the British colony of Vancouver Island, where, as elsewhere in the British Empire, slavery was forbidden.[1]

Vancouver Island and its satellites had become a haven for Black Americans, former slaves or not, fleeing persecution in their homeland. For a time in the 1840s, the Black community of the fledgling colony looked apprehensively across the water at the land they had fled. In those days, the slogan “54-40 or fight,” referring to the hoped-for annexation of the British possessions along the Pacific coast of North America, was on the lips and in the hearts of many an American expansionist. The Black population of Vancouver Island, who knew exactly how far American promises of freedom and equality extended, had good reason to fear that the “peculiar institution” would soon catch up with them.

Even in 1860, though the clamour for annexation had faded south of the border, Victoria’s Black pioneers had reason to fear the growth of American influence from another quarter. A reforming party, which was widely believed to be if not outright in favour of American annexation then at least friendly to American interests, was challenging candidates associated with the ruling Hudson Bay Company clique in the colonial elections in January of that year. The colony’s Attorney General, a member of the clique, fearing both the growth of American influence and the reforming party’s threat to the Company’s power, immediately enfranchised former American slaves living in the colony regardless of their term of residency on British soil, creating at a stroke a contingent of anti-American voters.[2]

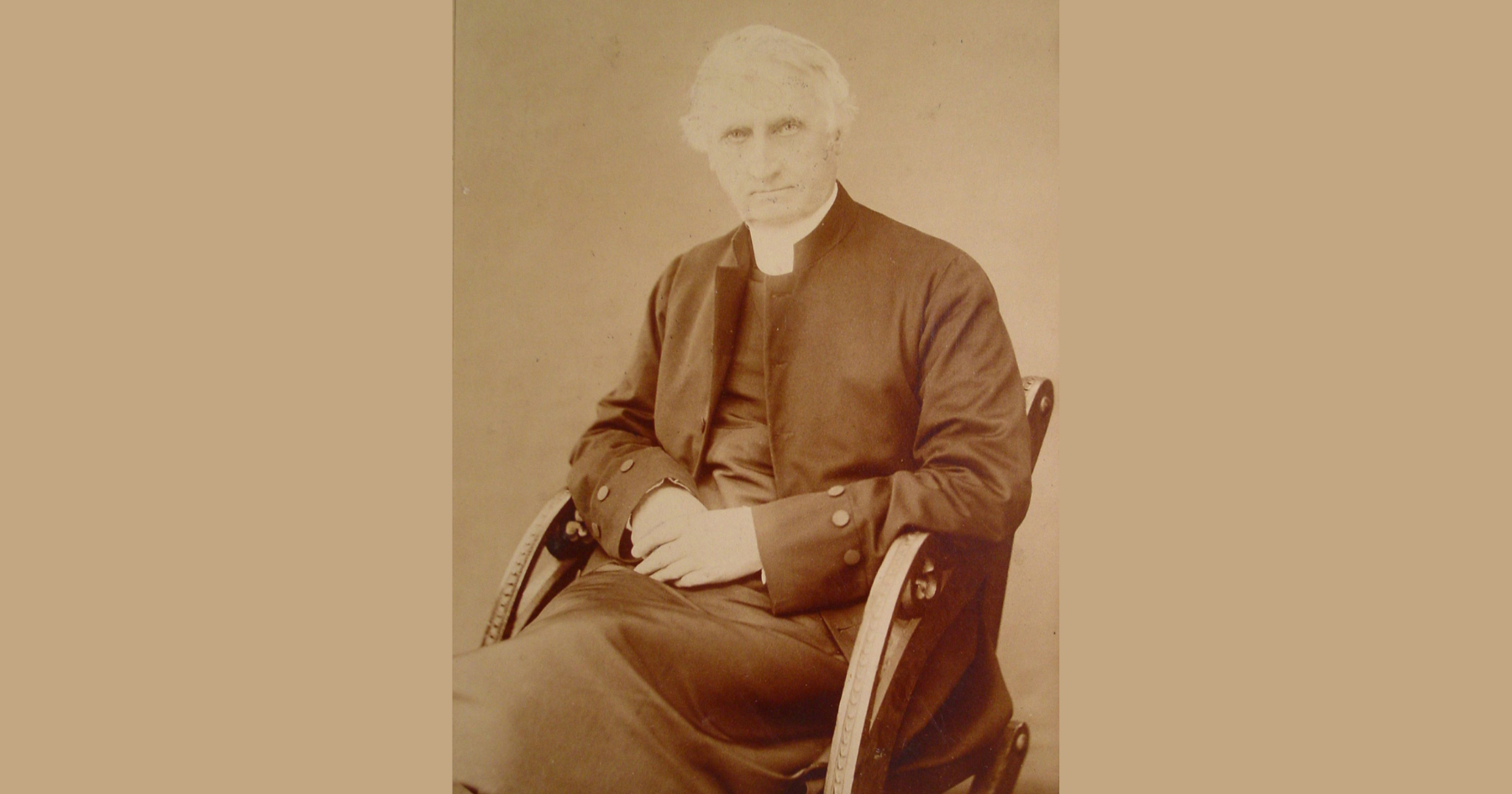

In the midst of the election campaign, on January 6, 1860, George Hills, first bishop of the Anglican Diocese of British Columbia, arrived in Esquimalt Harbour to take possession of his see. Hills felt little warmth for the cause of the reforming party and looked with repugnance on the attitudes of the Americans in the colony towards their Black neighbours. When the reform ticket was defeated, thanks in large part to the newly enfranchised British subjects, Hills reported back to England with obvious satisfaction that the pro-American party had been defeated by loyal Black voters.[3]

The racial divisions that afflicted the colony’s political life in 1860 were also felt in the church. American congregants expected segregated worship as a matter of course, and many of Victoria’s religious institutions hastened to accommodate this expectation. Bishop Hills, however, was firm in opposing any segregation in his diocese, assuring one anxious Black parishioner that “the Anglican Church would never make any distinction” on the basis of race.[4]

The bishop’s reasons for objecting to segregation were both patriotic and principled. On the first score, Hills the proud and loyal Englishman saw segregation as an offence against the British ideals of freedom and fair play. The same ideals had led the empire to abolish slavery in the first place, and Hills believed it his duty, as a subject of the Queen and a bishop of the English church, to further them. The contest between integration and segregation was, for the bishop, a contest between a noble “Christian and English sentiment” and a debased American prejudice.[5]

But more than this, segregation struck at the root of Christian spiritual equality. Black Christians were owed not distrust and revulsion, nor condescension and paternalism, but “honour and respect” as befitted “fellow immortals and equal[s] in the sight of God.”[6] Segregated worship, which would obscure this fundamental spiritual equality, was simply unchristian. Nor did Hills’ objection to the “colour distinction” stop at the lychgate: on learning that Black people were excluded from the Philharmonic and the YMCA, the bishop swore that “from whatever society they were excluded, I was excluded also, for I should belong to nothing where such unrighteous prejudices existed.”[7]

The bishop’s championing of integrated worship came at a cost. Many American Episcopalians refused to attend services at Christ Church Cathedral and expressed their horror — in language no longer fit to print — at the prospect of entering any church where they might be made to sit near their Black coreligionists.[8] Others made known their dissent with their pocketbooks: several people who had subscribed money for the building of Saint John’s Church reneged on their pledges, a loss which the bishop, presiding over the new diocese’s stretched finances, cannot but have felt keenly.[9]

Yet Bishop Hills’s opposition to segregation was not without its consolations, apart from the bishop’s vindication in the court of his own conscience. The bishop’s resolution won for him and his church the friendship and gratitude, sometimes tearful, of the colony’s Black community, and some prominent Black Victorians transferred their allegiance from Presbyterianism to the Church of England.[10] But doubtless the greatest consolation, for Bishop Hills and for us who are the heirs and stewards of his spiritual legacy, is this: the bishop’s vow that “the Anglican Church would never make any distinction” on the basis of race was a forceful witness in those infant years of British Columbia Anglicanism to a Christian ethic of spiritual equality that the church, in the century and a half since, has so often forgotten. God grant that we may never again forget this ideal nor flag in our efforts to see it realised.

Sources

[1] George Hills, No Better Land: The 1860 Diaries of the Anglican Colonial Bishop George Hills, ed. Roberta Bagshaw (Victoria: Sono Nis, 1996), p. 239.

[2] G.P.V. Akrigg and Helen Akrigg, British Columbia Chronicle, 1847-1871 (Vancouver, Discovery Press, 1977), p. 186.

[3] George Hills, An Occasional Paper on the Columbia Mission (London: Rivington, 1860), p. 13.

[4] Hills, No Better Land, p. 85.

[5] Hills, Occasional Paper, p. 13.

[6] Hills, No Better Land, p. 83.

[7] Ibid., No Better Land, p. 90.

[8] Ibid., p. 90.

[9] H.P.K. Skipton, A Life of George Hills, First Bishop of British Columbia, ed. Sel Caradus (Victoria: Christ Church Cathedral, 2008), p. 71.

[10] Hills, No Better Land, pp. 85, 90.