Confession, and Lent in its penitential character, is not about adding guilt or punishment to our suffering, but the removal of shame. We are liberated from the oppression of things done and left undone when we are able to face them plainly, and to accept reality as it is, rather than as we wish it could be.

We may fear that only bad people do the kinds of things we have done, and therefore we are bad people. If we can move beyond fear, we discover the truth of the difficulties of our lives, and of those whom we might judge. We are invited to live in a world where good people must work to be mindful of the harm we do, rather than one in which we can pretend such harm is impossible.

We hold on to our images of who we are, who God is, and what the world should be like, at times with an almost (or actually) anxious sense of certainty. We know who we are, however, not by mere inward belief, but by entering into relationship. As children, our personalities are formed by how others see us, and how we wish we were seen (and how we fear we are seen).

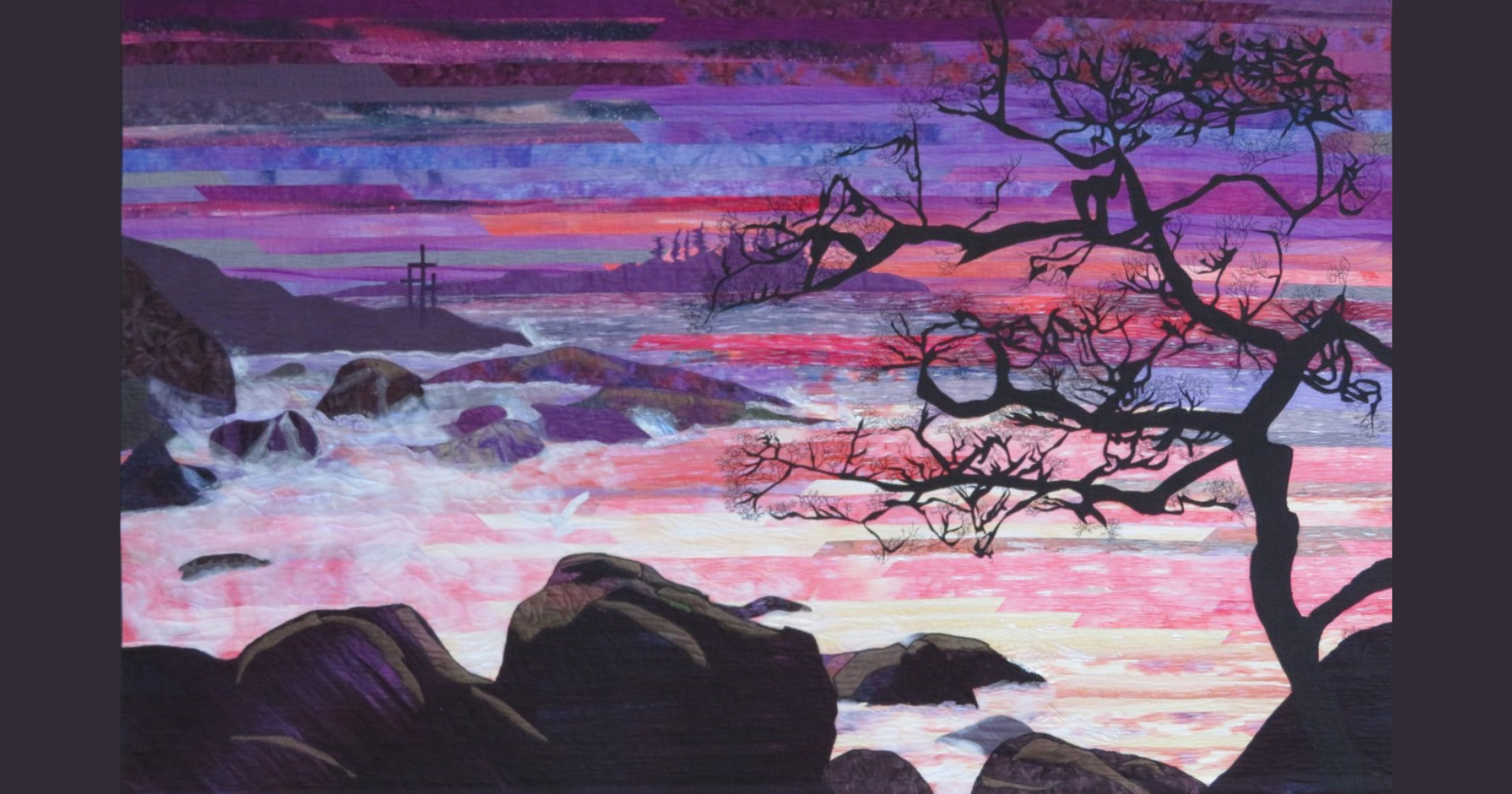

Our sense of self is also shaped by our theological imagination. In Christ we see the ultimate example of what a human life should be. And we see what calls to us in his life, and the lives of the many saints who make up the body of Christ. Relationships with loved ones and strangers across our lifespan, including our animal companions and all the wonders of creation, tell us who we are and who we might become.

We are not empty vessels who absorb these images passively. We are called to take account of and responsibility for what we have already done, and who we have already been, but not to limit ourselves. More often than not, we are already on the path to becoming the person we wish we were; over time, we grow to be like those we admire.

The images we carry with us and inhabit as we go out into the world affect those around us, the quality of our relationships and what the mirror of the world reflects back to us. Back and forth, our inner hopes and feelings and our outer interactions with all that exists, including God, are mutually transforming.

We can think theologically about how we know things in terms of “general revelation” and “special revelation.” The general is that which is accessible to everyone. It is the things we can see and directly encounter in the natural world. It is insights arrived at through the application of thought.

The special is that which is more directly conveyed, in one way or another, from the holy. This latter kind of revelation may come to a specific person, or through a specific means, rather than being generally accessible. We might think of prophecy, visions and any sort of private or supernatural experience of God as being forms of special revelation. We can also think in terms of general and special revelation in what we know of other people and ourselves.

What the world thinks it knows about us is largely down to general revelation: what they think they know about us from what they can see and what they can experience. Inside of us all, however, there is an inaccessible inner chamber, where the soul seems to find fit to dwell, where we experience the actual felt quality of our life and person. It is the place where we find ourselves in contact with God most deeply. We cannot readily move things from one realm into the other. At best, we can perhaps carry some images back and forth: who we are, who we might become.

In our hearts, we know that the world is wrong about us, and there are times when what the world reflects to us is a deeply hurtful ugliness. We come to know rejection and shame and the worst kinds of fear when our relationships tell us that we are fundamentally unacceptable, and that our lives have no value except as a vessel for others. This happens when someone else tells us how we ought to live and who they imagine we really are.

This Lent, so many of us are deeply disturbed by the rise in government persecution of trans people around the world. In the United Kingdom and the United States, and even in parts of Canada, new obstacles to the safety and well-being of trans people, and particularly trans youth, are emerging rapidly and being codified into law. It is worth taking some time to reflect theologically on gender as a site of revelation.

Like every aspect of identity, gender is always a matter of provisional knowledge, and like every category is somewhat unsound in its apparent concreteness. The experience and expression of gender changes across the lifespan and across different contexts.

A mother and a manager may be the same person but be expressed to others in completely different ways. Young children, teenagers, those who are building a household and those who are in retirement express and experience their sense of themselves, and their gender, quite differently. Gender expression in informal settings and formal settings can be very different for the same person.

To be a person is not to belong to fixed categories: good person, bad person; boy, girl or something else. Who we are is expressed, seen and felt differently across our lives and in different situations. In Lent, we are called to hold categories rather more lightly, and to allow ourselves to be surprised by the world as it really is, including who we are.

We are certainly not so wretched as we often feel, and we are not so innocent as we might sometimes like to project. We do not know others as well as they know themselves, but we might be an example to them as they seek to build themselves into the full stature of Christ. What we know and wish for in ourselves, in the inner sanctum of our being, is a special revelation from God that is to be treasured and shared.

Let us use the experience of Lent as a time to confess to ourselves and one another, not just with words but with our lives, who we really are, and what God has made known in our lives.